For most of us, our ancestors were immigrants from elsewhere. Researching their arrival and their place of origin may be easy, or nearly impossible, depending on the era and available records. In contrast to many types of records, we expect to find immigration information in a variety of sources. Always remember that there is no one record source where you can find an immigrant’s ancestral home. Rather, date and ethnicity determine where to look.

The requirements to immigrate and ethnic composition of U.S. immigrants varies over time. In colonial days, there were few requirements. Those who came from the various parts of the British empire may appear in no surviving records, because coming to the colonies was equivalent to traveling across state boundaries today. Those coming from outside British territories swore allegiance to the English king, which generated some records.

England, Ulster, Germany, Scotland, Ireland, The Netherlands, Wales, France and Sweden/Finland comprised most European immigrants from colonial times to 1790. However, Africans brought against their will as enslaved persons made up the largest group arriving in the U. S. during this time.

The law in effect at the time affects what records are available. Immigration rules changed with the Act of 1790, which excluded all non-whites from naturalization and imposed a two-year residency requirement for others before allowing citizenship. This requirement varied with different laws after 1790, first increasing to five years, then 14, and then back to five.

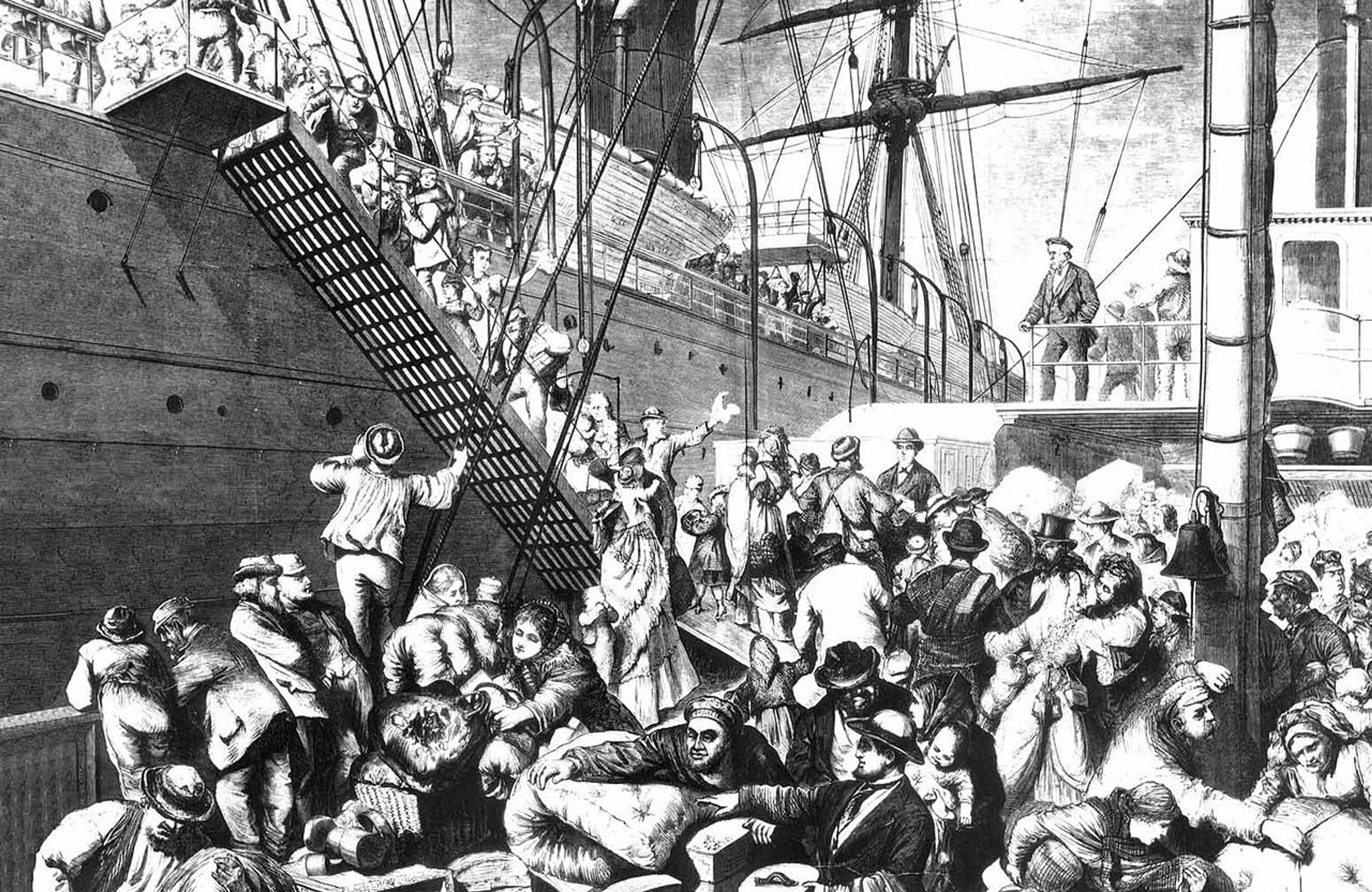

The 1819 Steerage Act required that ship captains create passenger lists. These lists are invaluable for genealogical researchers, although compliance was not 100% and some are lost. Most lists include name, age, gender, occupation, country of origin, destination and sometimes notes. Irish, German and some other European groups dominated immigration until 1890, and the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882 barred Chinese immigration.

The 1891 Immigration Act directed that more information be included on passenger lists, with the addition of marital status, last residence (town name), final U. S. destination, where, when and how long passengers had been in the U. S. before and the name, address and relationship of a relative if they were joining one. Researchers should remember that officials created passenger lists in the port of departure, not arrival. Thus, the myth of name changes by officials at arrival is incorrect. Spelling, however, may have been incorrect, or later employers or the immigrant may have simplified or anglicized the name. A timeline of immigration laws and details is at: www.migrationpolicy.org/sites/default/files/publications/CIR-1790Timeline.pdf.

Immigration proceeds with multiple steps, all of which might generate records for family historians. Depending on the country of origin, emigrants may need permission to emigrate, which may be in either civil or church records. If the emigrant faced deportation as punishment for crimes, seek convict transportation records. Some emigrants crossed multiple borders, potentially generating paperwork each time. Payment records to carriers (usually ships) may exist — some required payment up front, others by indenturing themselves at the destination. The most common paperwork is the ship’s manifest or passenger list. At arrival, newspapers may have posted notices or lists of those arriving, or immigrants may have given oaths of allegiance. In some cases, legal actions related to the passage exist in court records. Churches, newspapers or land records might record arrival of new residents. For 19th Century and later immigrants, declaration of intent followed by naturalization created records. Finally, immigrants needed a passport to travel in some cases, or to return on visits to the home country.

The first step in researching an immigrant ancestor is to assemble all you know about them. This includes birth and marriage dates (or other events in the country of origin), place of origin, information about relatives, family traditions or heirlooms connected to immigration, the friends, relatives, associates and neighbors, their ethnicity and name changes. Census records often have some of these, or approximations to them. Then, gather all you can find about approximate date, departure place, arrival port, ship and reason for migrating. You will identify gaps in the process, which point toward research goals.

Learn some historical background for both the departure and arrival place, emphasizing the time your ancestor immigrated. It is important to remember some features of immigration that may assist your research. In some cases, immigration moved in multiple steps, with people spending time in one location, then moving to another. Others returned home, or sometimes returned home, then came back to the new country. People usually immigrated in communities, which may have extended over time (today we call this “chain migration”).

Bill Eddleman, Ph.D. Oklahoma State University, is a native of Cape Girardeau County who has conducted genealogical research for over 25 years.